A nice article from Scott Mendelson at Forbes:

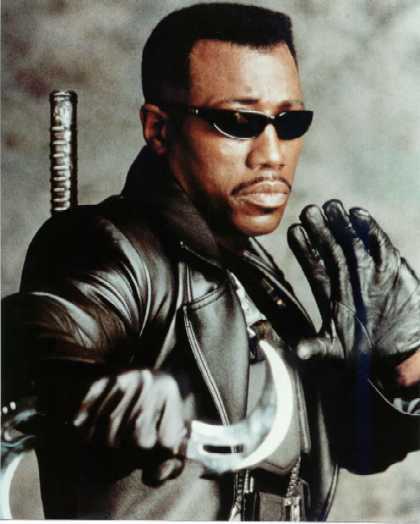

As promised, here is the sequel to the piece I wrote last month concerning the post-Batman phase of comic book movies. If you’re stumbling onto this by happenstance, you might want to read the original first and come back. Today marks the fifteenth anniversary of the release of New Line Cinema’s Blade. By itself, that’s not a particularly important occasion. Blade is a solid enough action picture, and its curtain raiser rave sequence is pretty terrific. A week after I watched The Avengers, I was relieved to see a big-budget fantastical action movie that was actually competent. Fifteen years later, Blade is still one of the few major comic book franchises to both star a person of color in the lead and be R-rated. While it was arguably sold as an action vehicle for Wesley Snipes that happened to be based on a Marvel comic book, it’s success kick-started the second era of comic book cinema.

What was different about Blade, aside from the fact that it was the first time that a Marvel comic book superhero had been successfully adapted to the big screen in recent memory, was that it was both set in the present day and based on a comic book that actually had somewhat of a genuine fan base in America. It differed from the likes of The Phantom or The Rocketeer by actually being a comic character that kids may have actually heard of prior to seeing the film, if only through his appearances on Fox ‘s Spider-Man cartoon in the mid-1990′s. Its $18 million debut and $70m domestic finish ($131m worldwide) on a $45m budget opened the doors to the modern comic book movie, and it was arguably the first major success of this second phase.

Ironically, in the two years that would span between Blade and X-Men, we had two would-be variations of a trend that hadn’t really started yet. In summer 1999, Universal spent $68 million on Mystery Men, hoping to score by spoofing the modern-day superhero genre. Yet said genre didn’t actually exist quite yet, so most audiences didn’t get the joke and the film sadly tanked ($33m worldwide). In April of 1999, we had The Matrix, which was less a pure deconstruction and more a pure stripped down-to-the-core science-fiction variation on Joseph Campbell’s heroic journey (it’s the most beat-for-beat adaptation I’ve seen in modern times). It, like Robocop or Darkman before it, was a pure comic book superhero film that wasn’t actually based on a comic book.

And just four months after 20th Century Fox blew open the doors of this second wave with X-Men, M. Night Shyamalan’s (still fantastic) Unbreakable was the ultimate ‘real world’ superhero film, stripping down the origin story elements to their very core while ruminating on the philosophical and myth-based folklore that gave rise to these kinds of stories in the first place. But just months after X-Men and 36 months before Spider-Man, it was a deconstruction of a genre that barely existed, which rendered it quizzical to much of the public (it still made $250m worldwide, natch). But Blade led to 20th Century Fox’s X-Men, which led the way to Sony ‘s Spider-Man, after which it was open season on this next phase of comic book superhero adventures. What separates this second wave of comic book adventures from the post-Batman era is two-fold.

First, the likes of Spider-Man, Batman Begins, Fantastic Four, and Superman Returns are all set in the present-day, taking places in somewhat realistic variations on our world today. They are not 30′s/40′s-set period pieces in the vein of Paramount’s The Phantom, Disney’s Dick Tracy, or Warner Bros.’ Batman (which, as you may recall, plays like a 1940′s film noir), but rather stories of superheroes in our world in our current time. They were also allegedly more faithful to the source material, although I’d argue that increased source fidelity was a marketing-driven myth. Come what may, Batman Begins is no more or less faithful to the various Batman comics than Batman Returns. But, organic web-shooters aside, the meme was that this new batch of superhero films were made by and for fans with utmost respect for the source material.

Second of all, these were not adaptations of long-forgotten pulp heroes that only your parents or grandparents remembered reading in their original forms, they were adaptations of the very superheroes that our generation grew up with and still enjoyed in the present tense. We watched the Fox Spider-Man cartoon series and/or played the six-player X-Men arcade game and were introduced to these iconic characters outside of their four-color origins. We were primed for feature film adaptations by secondary media sources in a way not available to The Shadow or Dick Tracy. Our parents may have grown up with Dick Tracy, but we couldn’t stop humming the opening theme to Fox’s X-Men cartoon. What also distinguishes this next batch of big-budget superhero films was the time in which they were made. Technology, special effects, and film making wizardry had progressed to a point where we could actually see Spider-Man swinging across New York City, Night Crawler ‘bamfing’ from one spot to another, and the Hulk tossing a tank into the desert.

Also of note, every major comic book film after the first X-Men was released in the shadow of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Spider-Man somewhat benefited from the attacks at the box office, as it had the “good fortune” to be the distinctly American, relentlessly optimistic, New York-centric adventure film that audiences were clamoring for. And pretty much every superhero film after had to directly or indirectly deal with the aftermath of what happened that Tuesday. Be it the inherent sacrifice of heroism (Spider-Man 2), standing up to extremists by being morally superior (Batman Begins), finding a common ground with your enemy (Blade II), or the varying degrees of acceptable self-defense against an immoral government agenda (X2), the next batch of superhero adventures all had to cope with a far more complicated picture of America’s alleged righteousness and/or their existence in a world where evil so readily triumphed over good (Superman Returns). The thematic connective tissue of most of these films lies in their attempts to remain relevant post-9/11, just as the first comic book superheroes had to assimilate to the new found reality of World War II.

What is interesting about the box office fortunes of these films is how not all-encompassing these superhero films were. No X-Men picture grossed as much as (for example) Night at the Museum while most of the C-level characters starred in films that more-or-less broke even (Ghost Rider $228m on a $110m budget) or disappointed (The Punisher $54m/$33m). Even Superman Returns‘s $392m worldwide gross couldn’t compensate for its inflated $270m budget. Hulk opened to $62m, but couldn’t get past $245m on a $135m budget. Even Batman Begins wasn’t a major smash, earning $375m on a $150m budget and earning a sequel only through its leggy run and strong DVD sales. Hollywood spent a decade chasing Spider-Man and its $750m-$890m gross, but really none of these phase 2 films came anywhere near Peter Parker.

It wasn’t until what is arguably phase three, the ‘connected-universe era’, began with Iron Man in May of 2008 that superhero films started earning enough to justify their superlatives. But that’s for another day, since we still have a few years to see how that plays out. For the moment, let us give a toast to Stephen Norrington’s Blade. It was not the biggest of anything or the best of anything. But it was a shining example of a rock-solid comic book adaptation that showed what could be done within the realm of the genre as technology caught up with the four-color world. Its success kicked off the second wave of superhero films, one where we could actually thrill to seeing the heroes we grew up with on the big screen rather than merely living out the period-piece adventures of our elders.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.